WashU physicists have created a new phase of matter in the center of a diamond.

In their ongoing efforts to push the boundaries of quantum possibilities, physicists at WashU have created a new type of “time crystal,” a novel phase of matter that defies common perceptions of motion and time.

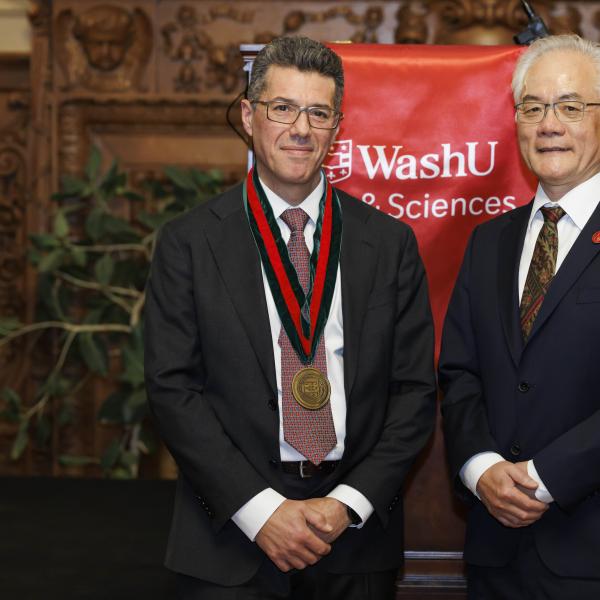

The WashU research team includes Kater Murch, the Charles M. Hohenberg Professor of Physics, Chong Zu, an assistant professor of physics, and Zu’s graduate students Guanghui He, Ruotian “Reginald” Gong, Changyu Yao, and Zhongyuan Liu. Bingtian Ye from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University’s Norman Yao are also authors of the research, which has been published in the prestigious journal Physical Review X.

Zu, He, and Ye spoke with the Ampersand about their achievement and the implications of catching time in a crystal.

create a time quasicrystal, a new phase of matter that repeats

precise patterns in time and space.

What is a time crystal?

To understand a time crystal, it helps to think about familiar crystals such as diamonds or quartz. Those minerals owe their shape and shine to their highly organized structures. The carbon atoms in a diamond interact with each other to form repeated, predictable patterns.

Much like the atoms in a normal crystal repeat patterns in space, the particles in a time crystal repeat patterns over time, Zu explained. In other words, they vibrate or “tick” at constant frequencies, making them crystalized in four dimensions: the three physical dimensions plus the dimension of time.

What makes a time crystal special?

Time crystals are like a clock that never needs winding or batteries. “In theory, it should be able to go on forever,” Zu said. In practice, time crystals are fragile and sensitive to the environment. “We were able to observe hundreds of cycles in our crystals before they broke down, which is impressive.”

Time crystals have been around for a little while; the first one was created at the University of Maryland in 2016. The WashU-led team has gone one step further to build something even more incredible: a time quasicrystal. “It’s an entirely new phase of matter,” Zu said.

How is a time quasicrystal different from a time crystal?

In material science, quasicrystals are recently discovered substances that are highly organized even though their atoms don’t follow the same patterns in every dimension. In the same way, the different dimensions of time quasicrystals vibrate at different frequencies, explained He, the lead author of the paper. The rhythms are very precise and highly organized, but it’s more like a chord than a single note. “We believe we are the first group to create a true time quasicrystal,” He said.

How are time quasicrystals created?

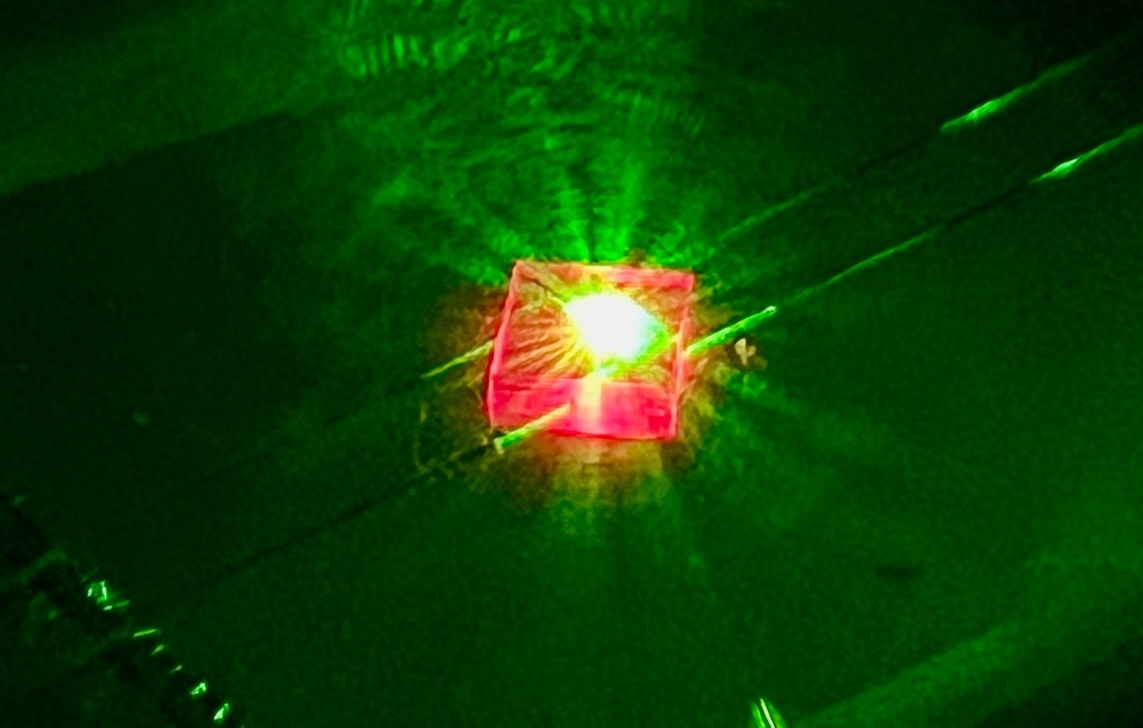

The team built their quasicrystals inside a small, millimeter-sized chunk of diamond. They then bombarded the diamond with beams of nitrogen that were powerful enough to knock out carbon atoms, leaving atom-sized blank spaces. Electrons move into those spaces, and each electron has quantum-level interactions with its neighbors. Zu and colleagues used a similar approach to build a quantum diamond microscope.

The time quasicrystals are made up of more than a million of these vacancies in the diamond. Each quasicrystal is roughly one micrometer (one-thousandth of a millimeter) across, which is too small to be seen without a microscope. “We used microwave pulses to start the rhythms in the time quasicrystals,” Ye said. “The microwaves help create order in time.”

What are the potential uses of time crystals or quasicrystals?

The mere existence of time crystals and quasicrystals confirms some basic theories of quantum mechanics, so they’re useful in that way, Zu said. But they might have practical applications as well. Because they are sensitive to quantum forces such as magnetism, time crystals could be used as long-lasting quantum sensors that never need to be recharged.

Time crystals also offer a novel route to precision timekeeping. Quartz crystal oscillators in watches and electronics tend to drift and require calibration. A time crystal, by contrast, could maintain a consistent tick with minimal loss of energy. A time quasicrystal sensor could potentially measure multiple frequencies at once, creating a fuller picture of the lifetime of a quantum material. First, researchers would need to better understand how to read and track the signal. They can’t yet precisely tell time with a time crystal; they can only make it tick.

Because time crystals can theoretically tick forever without losing energy, there’s a lot of interest in harnessing their power for quantum computers. “They could store quantum memory over long periods of time, essentially like a quantum analog of RAM,” Zu said. “We’re a long way from that sort of technology, but creating a time quasicrystal is a crucial first step.”

Learn more about quantum science at WashU

Much of the quantum research at WashU is taking place through the Center for Quantum Leaps, a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan. Launched in 2022, the CQL is working to pursue novel research in the areas of astrophysics, quantum devices, and quantum computing algorithm development. Read more about WashU’s quantum quest.