Sophomore Gracie Hime reflects on her experience studying Dante’s Inferno this semester in a course taught by Michael Sherberg.

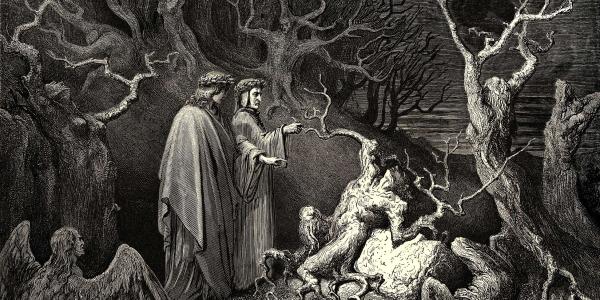

After a semester in a class on Inferno, the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy, it has become clear that one term is not enough time to fully explore even the surface level of this epic poem. By virtually following Dante and Virgil on their descent into hell, readers can’t help but spiral into (pun intended) a pool of questions about their own life and existence. While this work is supposed to encourage self-reflection, I’ve learned that like every piece of literature – especially those on religion – Inferno be read in a way that doesn’t focus on the individual experience, but rather on the experience of humans in a world where individualism is prioritized.

Dante encourages us to interpret and investigate the comedy in a multitude of ways beyond that of merely reading verses. In a letter to his friend Cangrande della Scala, Dante defines four ways to read Inferno, and in reality, any work of literature: literally, allegorically, morally, and anagogically. As a book worm and classics enthusiast, I felt pretty versed in deep reading literature. But, as I discovered throughout the course, it takes more than just analytical and creative deep reading when it comes to Dante; this really pushed me. I was caught off guard when we reached a point late in the text that had a convoluted reference to something in the beginning. In plain text and without mentorship, these two scenes seemingly had no connection or reference to one another, but after diving into the several layers each moment incapsulated, I became blown away that someone discovered this connection.

"Talking about this literature with a class full of diverse people with unique backgrounds provided even deeper collusions and confusions, fueling conversations that made me question my understanding."

Luckily, the class was instructed by Michael Sherberg, a scholar of 14th- and 16th-century Italian literature and professor of Italian, making it significantly easier to follow the unsolved case that is Dante’s Inferno. Sherberg’s interest has focused on Dante and the poet’s acknowledgment of this loaded period of time. “The early 14th century fascinates me because so much is happening. One thing that interests me about Dante is that he seems to be aware that the world is slipping into a future he's not happy with. So, we can see him as a reactionary or as admirably anti-materialist, depending on our point of view.”

‘So much is happening’ is the truth – there’s really no better way to describe Dante and his experience in hell. Between the complex layout of hell, to the contrapasso (the reciprocal and intentional punishment asserted towards each sin), and the numerous familiar characters, readers are stuck in what seems like complicated sci-fi lore. All of these aspects contribute to the somewhat guilty pleasure it brings to conspire about a dark and gory afterlife. It’s like watching a horror movie or going through a haunted house: our brains can’t help but love fear and be compelled by things that disgust.

Dante spares only the details that are beyond the capacity of mere human language, leaving only the most vivid scenes to amuse our brains. At all points, he knows exactly what he is doing to his readers. He makes us feel sympathy towards people who deserve none, makes readers compare themselves to characters in hell, and even pushes us to question what ring we would be most likely to be banished to. Beyond being an aid to helping people become Christians, Inferno allows even the most nonreligious to reflect on their own concepts of human nature.

The blatant deceitfulness, vanity, and hypocrisy that Dante exhibits in even choosing to write this poem is entertainingly ironic, but again, focuses in on the undeniable fault of humans. I found myself scoffing at Dante’s actions and tendencies yet couldn’t help but dive into the deep and complex imagination of the afterlife. Talking about this literature with a class full of diverse people with unique backgrounds provided even deeper collusions and confusions, fueling conversations that made me question my understanding. This is the exact type of experience I look for in a discussion-based literature course, whether or not it includes a journey to hell.