In his most recent book, Hayrettin Yücesoy confronts a dominant historical narrative that depicts the political thought and practice of Muslims in a rigid religious framework. Examining the concepts of secularity and good governance in premodern times, he extends their boundaries beyond the confines of Europe.

For Associate Professor Hayrettin Yücesoy, a scholar of Middle East history and Islamic studies, the quest for a brighter future always involves a journey to the past.

"To establish a more equitable society, we must continue to open new windows on the past," Yücesoy said. "We can forge pathways toward improved futures only by liberating ourselves from the grip of hegemonic narratives."

In his new book, "Disenchanting the Caliphate: The Secular Discipline of Power in Abbasid Political Thought," Yücesoy challenges the dominant historical narrative of "Islamic political thought," arguing that it reduces the histories of Muslim people to their religious cultures.

“Circulating widely since the late 19th century, the invented liberal nomenclature ‘Islamic political thought’ renders an important secular thought tradition invisible,” Yücesoy said. “My book resists the prevailing colonial and nativist narratives that continue to portray religious scholars as the only authentic representatives of the political tradition.”

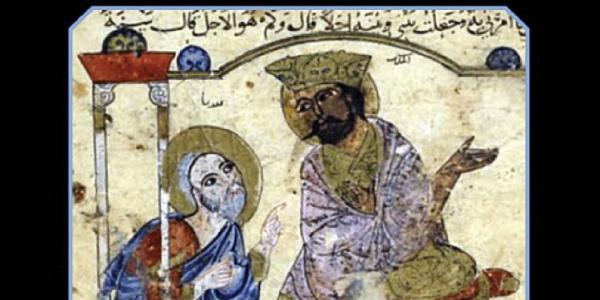

To dispute this conventional history, Yücesoy revisits Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman texts, with a focus on political tracts from the eighth and ninth century. In this exploration, he uncovers a previously overlooked tradition of secular political thought, commonly referred to as "siyasa."

“In siyasa literature, the idea of good governance began to diverge from religious concerns,” Yücesoy said. “A wealth of this literature emerged between the eighth and 16th centuries, surpassing the volume of political literature produced in Europe during the same era. But this major political thought tradition is largely neglected.”

The siyasa tradition has historically been overshadowed by a religious political tradition called “imamate discourse,” according to Yücesoy. While imamate discourse was produced by religious scholars called “ulema,” siyasa emerged from state bureaucrats and lay intellectuals who were critical of the ulema.

Natives of regions once conquered by the caliphate, siyasa authors were often integrated into the empire’s bureaucracy due to their proficiency in the conquered regions’ languages — Persian, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic. As a result, they found themselves in a precarious social position.

"These scholars inhabited a socio-political realm that granted them privileges but forced them to navigate between two identities: one conferred by birth as subordinate imperial subjects and another earned through their work and talents as members of the ruling class," Yücesoy writes.

The consequence of this remarkable position, according to Yücesoy, was the production of a political knowledge that placed greater emphasis on the pragmatic elements of governance, aiming to secure the consent and satisfaction of imperial subjects. This was a departure from the religious scholars' approach, which prioritized the implementation of religious edicts with the goal of compliance as an end in itself, regardless of the outcome.

"In the eyes of lay literati, religious mandates did not extend to matters of politics," Yücesoy said. "They scrutinized the political landscape and, rather than relying on religious guidance from the ulema, sought practical solutions advocating political prudence, which included the rational assessment of political challenges to find an agreeable course of action.”

In such an approach, Yücesoy claims, siyasa stands in stark contrast to much of the political advice literature, which predominantly highlights strategies to enhance the ruler's capacity to maintain power. On the contrary, the proponents of siyasa in his study imagine governance as an art that opposes oppression and the use of brute force solely for the purpose of control.

Yücesoy compares the political writings of a prominent siyasa bureaucrat-intellectual, Ibn al-Muqaffa', with a renowned political treatise, "The Prince," written by the Italian diplomat Machiavelli. "While Machiavelli addressed a 16th-century prince regarding specific political circumstances, Ibn al-Muqaffa' pursued a similar objective in the eighth century: persuading a caliph to make informed decisions on critical political questions," Yücesoy said.

Both Ibn al-Muqaffa' and Machiavelli were profoundly influential scholars who laid the foundations for secular political traditions in their works, according to Yücesoy. But Ibn al-Muqaffa' is much less known — a misfortune that Yücesoy attributes partly to the legacy of the Orientalist scholarship.

“In studying the cultures and peoples of the world, Orientalists created a dichotomy between Europe and ‘the Orient,’” he said. “Secularity became a case in point to distinguish between ‘the West’ and ‘the East.’” As a result, the Muslim people were defined as “religious,” and everything in their histories became entangled with that label.

"If you were to open any article or book on political thought in the histories of Muslims, you would invariably encounter the label 'Islamic political thought,'” Yücesoy said. “To appreciate the potential misrepresentation inherent in this label, imagine calling the European political tradition 'Christian political thought.' When you frame the conversation in this way, you precondition yourself to perceive every facet of this history through a religious lens. Once you adopt the perspective of a hammer, everything tends to look like a nail to you."

Like the siyasa tradition, Yücesoy believes that the field of Islamic and Middle Eastern studies has been significantly advanced by scholars who reflect critically on their backgrounds and social positions. "The pivotal moment comes when one begins to reflect upon one’s own background — one’s culture, sociopolitical context, various roles and positions in society, and the academic traditions from which one hails," he said. "I believe that true intellectual freedom is a continuous self-reflective journey."