Undergraduate researcher Sam Ko has been studying ticks for the last year of her college career. Her legacy will be confirming the arrival of a tiny invasive species raising big concerns.

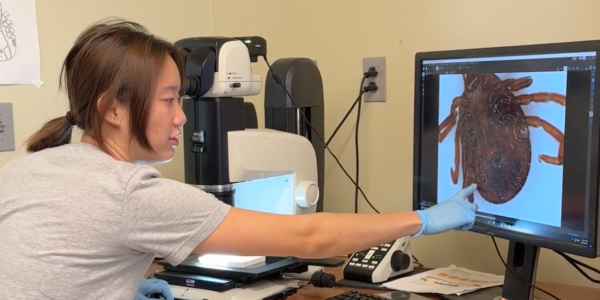

To the untrained eye, the ticks that crawl through the Missouri woods mostly look alike. But when Sam Ko, an undergraduate research fellow at Tyson Research Center, put a particular tick under a microscope in July 2024, she immediately realized she was looking at something special: the long-anticipated, much-feared Asian longhorned tick, an invasive species whose arrival would soon make headlines.

With the tick’s image displayed on a monitor at 100x magnification, Ko saw all of the tell-tale signs: The female tick was smaller than the common lone star ticks that call Tyson home, it lacked the white spot that adorns the backs of female lone star ticks, and it had small appendages (palps) sticking out sideways from the sides of its heads — the “horns” that give the longhorned tick its name. “The palps were much different than any other tick species known to be in the area,” she said. In short, it ticked all the boxes.

“It was a longhorned tick, the first one ever found in St. Louis County,” said Ko, a senior in environmental biology who has been studying ticks for more than a year. “It was cool to make the discovery, but I also knew it wasn’t a good thing to see. There will be more, and it could have potentially large effects on the ecosystem.”

The longhorned tick, native to East Asia, was an unwelcome but not unexpected find. In a lab at Tyson, “be on the lookout for longhorned ticks” is scrawled on a whiteboard next to Ko’s microscope. The message, written in 2023, was inspired by the relentless westward spread of the species after it was first detected on the East Coast in 2017. The first specimen in Missouri was found in rural Greene County in May 2021.

Light brown and about the size of a sesame seed, the longhorned tick can live for months without a meal. Unlike lone star ticks and other native species, female longhorned ticks can lay eggs — sometimes 2,000 a week — without mating, a process called parthenogenesis. “The ticks are well equipped to reproduce and spread very quickly,” Ko said.

The longhorned tick discovered at Tyson was hanging out near a moist, dense, shady thicket of pawpaw trees, a preferred habitat for native lone star ticks. Ko commuted to the spot on a Polaris UTV, down narrow dirt roads through Tyson’s hickory and oak trees and past World War II-era concrete bunkers once used to store ordinance.

Wearing gaiters over her hiking boots to discourage tiny hitchhikers, Ko walked into the woods toward the pawpaw patch. (Ticks likely favor this spot partly because the plump pawpaw fruits attract potential prey, she explained.) Waving a sticky flag-like cloth through the underbrush, Ko collected dozens of ticks in just a few minutes. She then used a lint roller and tweezers to collect each specimen for later analysis under a microscope in the Tyson labs.

The arrival of the longhorned tick in St. Louis County raises new concerns for humans, pets, wildlife, and livestock. In other countries where the tick is widespread, it can carry viruses that cause illness and even death in humans and cattle. So far, it’s unclear what diseases the ticks might carry in the U.S., but researchers are closely monitoring the possible threats.

With support from a Transcend Initiative Grant award from WashU’s “Here and Next” seed grant program, Ko and other researchers are stepping up the search for longhorned ticks this spring. In addition to gaining a better understanding of the spread and ecology of the tick, they hope to take a thorough inventory of the viruses and other pathogens carried by the invasive species.

The lead researchers on the project are Solny Adalsteinsson, a senior scientist at Tyson Research Center; Jacco Boon, a professor of medicine, molecular microbiology, and pathology & immunology at WashU Medicine; Michael Landis, an assistant professor of biology; and Susan Flowers, the outreach, education, and inclusivity coordinator at Tyson Research Center.

In 2024, the St. Louis County Department of Public Health and Parks and Recreation launched a program that allows the general public to deposit ticks found at Lone Elk, Queeny, and West Tyson parks in a drop-off box. In the first year, the program collected about 300 ticks, almost all of them lone stars.

For now, people and pets who venture into Missouri woods and grasslands are unlikely to run into longhorned ticks, but they should still take precautions — especially in the tick-heavy seasons of late spring through early fall. Ko recommends using bug spray, tucking pants into socks in brushy or grassy areas, and checking regularly for ticks on skin or clothes. At Tyson, she often uses strips of duct tape to remove ticks from her clothes.

After she graduates in May, Ko plans to work with Adalsteinsson as a co-mentor for the tick and wildlife team for their summer field season at Tyson, the next step in her plan to eventually achieve an advanced degree in environmental studies.

For now, she has more ticks to collect. She’s well aware that the bugs are dangerous, but she can’t help being fascinated by the small, resourceful creatures. She even wrote her senior thesis on them.

“Ticks are very closely connected to the plants and animals of the ecosystem,” Ko said. “The more you learn about something, the more interested you become. That’s what happened with me.”