Rebecca Messbarger reflects on Trump, Twitter, and Frankenstein.

Next year, the world will mark the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein, Mary Shelly’s enduring vision of the ruinous consequences of modernity divorced from human welfare.

It is a cautionary tale for our time.

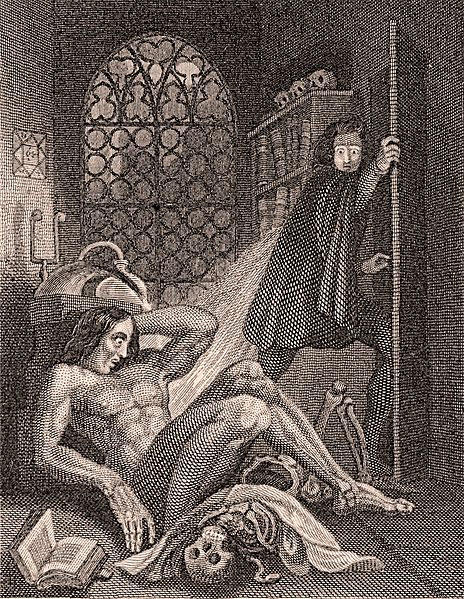

The tragedies strewn across Shelley’s novel are born of the reckless ambition of Victor Frankenstein, who exploits the latest tools of science to conquer death. In the malignant gloom of his laboratory, he bends the force of lightning to his intellectual will. Frankenstein’s obsessive, self-glorifying pursuit of “the spark of being” is a perversion of the Enlightenment promise to better the human condition through scientific discovery. He, not science or his creature, is the real monster.

Flanking experimental science, among the most brilliant ‘sparks’ to animate the Enlightenment Age was public opinion--a potent new rival to State and Church authority, without which contemporary democracies would never have been born. Although Shelley did not conjure a monster from the corruption of public opinion, perhaps nothing better exemplifies our Modern Prometheus than the warping of democratic discourse and weakening of the press by the unrestrained channels of social media.

During the 18th century, public opinion expressed itself on the printed pages of emergent newspapers and journals, often read in such novel public spaces as the coffee house. Here, citizens from disparate social classes could, as in no previous age, mix, exchange ideas, and critique the traditional social and political order.

The effect of this cultural turn can be seen exemplified by a group of young Enlightenment thinkers in Milan. Organizing themselves into the Academy of Fists, their aim, as their name suggests, was to thump the nose of the ruling elite and usher in a new era of reform that would advance the common public good.

The Fists called for sweeping reforms of staid institutions in tracts read across Europe and across the Atlantic. The most famous of these was Cesare Beccaria’s On Crimes and Punishment that demanded an end to the “fury and fanaticism” of state sanctioned torture and capital punishment.

In 1764, the Fists launched Italy’s most important Enlightenment journal, The Coffee House (Il Caffe´), so named to signal their focus on current issues of practical import for the broadest possible readership, from the “young maiden” to the “lofty magistrate.”

Their motto, “things not words,” prized practical action over academic rhetoric. Spreading well beyond the Italian peninsula, these ideals informed the public discourse that helped forge our nation. They also continue to underpin contemporary protests from the Middle East to cities throughout our nation.

Daily we are witness to the staggering power of social media to amplify public opinion and the force of its political impact in defense of democratic liberties beyond anything imaginable in the eighteenth century.

Yet, despite its immeasurable promise, when unmoored from the ideal of the public good, the networked public sphere subverts participatory democracy as in no other time. Twitter most blatantly manifests this paradox as it gives vent at once to cries of popular revolution and the voice of political revulsion.

Much has been written about the impact that social media platforms had on the lightning strike ascension of Donald Trump to the presidency, and on his twitter-driven statecraft in the weeks since. Although post-election statements by the likes of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg insist that social-networking sites will work to stem the negative influence of misinformation and false news, it seems clear that the magnitude of that influence is incalculable and, indeed, uncontrollable.

In a twist of irony, Shelley’s novel ends with her monster lamenting that he has no mate to share his life, “no Eve soothed my sorrows nor shared my thoughts.” At their best, social media tools have created millions of new human connections and mobilized citizens, often the most marginalized, against repressive power structures.

But like other radical technological innovations in history, they are in the hands of good and bad actors alike and have taken on a life of their own. When unleashed as a monster of self-reference and egotism hostile to the genuine exchange of ideas -- when deployed to undermine or obliterate the truth, this irrepressible 21st-century technological revolution of the public sphere looms menacingly over the democratic body politic.

It is a monster of our own creation.

_

Rebecca Messbarger is professor of Italian, history, art history, performing arts, and women, gender, and sexuality studies. She is director of medical humanities.