In a new book, ethnomusicologist Patrick Burke examines 1960s popular music and radical politics.

White rock musicians in the late 1960s imitated Black Power activists in ways that were both supportive and appropriative, writes Patrick Burke in a new book about popular music and radical politics. Tear Down the Walls: White Radicalism and Black Power in 1960s Rock explores how bands like the MC5 and Jefferson Airplane dialogued with — and frequently mimicked — radical political movements in Black communities.

Burke, associate professor of ethnomusicology and chair of the Department of Music, noted that appropriation has always been a defining trait of American popular music. “The whole history of American popular music is arguably built on this dynamic where white musicians who are invested in some aspect of Black pop music either imitate outright or borrow aspects of it,” Burke said. “In every new genre that comes along, whether it's ragtime or swing or rock and roll, there is some element of that dynamic going on.”

In the 60s, rock musicians began to think of themselves as more politically active at the same time that rock music began to be more inventive in the kinds of statements it made. LPs became the defining artistic statement of rock bands, replacing 45-rpm records that marketed individual tracks. “Rock’n’roll is starting to turn into rock,” Burke said. “These bands aren’t trying to record hit singles so much as they are trying to put out serious artistic statements that deal with politics.”

By 1968, many white musicians, aware of the history of cultural appropriation in rock music, sought out ways to move beyond the mere imitation of Black artists and instead contribute to civil rights causes. White rockers started dressing like members of the Black Panther party, with dark clothing, leather jackets, and a more militaristic style becoming common. The music began to reflect — and sometimes advance — these new political aspirations by providing a kind of soundtrack for the white radical movement.

In Tear Down the Walls, Burke singles out Jefferson Airplane as one band that tried to move past appropriation in their music, even as their fashion and messaging remained appropriative of Black political movements. Their lyrics often included revolutionary rhetoric, Burke notes, but they rarely translated that rhetoric into political action. Despite this inaction, the band found ways to dialogue meaningfully with the cultural modes to which they were indebted.

“Jefferson Airplane didn’t simply copy blues motifs from Black musicians like many of their contemporaries did,” Burke explained. “They had a more hybrid approach that blended blues, jazz, and R&B. They weren’t trying to ‘sound Black,’ although their music drew heavily on Black influences.”

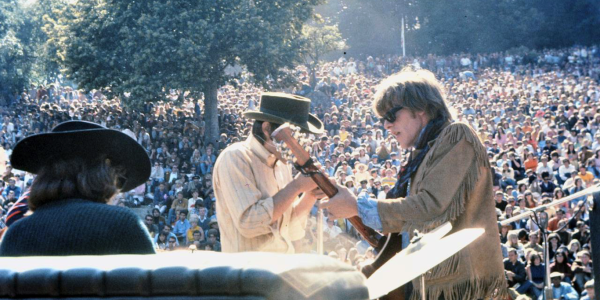

Burke also writes about the MC5, who for a time served as the house band of the White Panthers, a group that modeled itself after the Black Panthers and tried to further the same causes. The White Panthers overtly imitated the Black Panthers, using the same organizational structure with their own ministers of war and propaganda. The MC5 were, for a brief moment, both a fairly important band who appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine and also acted as the official propaganda arm of a radical political organization.

In a now infamous story, the MC5 got into a fight with another band outside of a club in 1968 about which group was more radical. During the fight, limousines sent by MC5’s record label arrived to take the band members back to their hotels.

“The MC5 represent this moment when you could be both a radical revolutionary and a rock star, but people were starting to think that maybe being both at once wasn’t actually possible, that maybe signing to a record label is something very different from being a radical,” Burke said.

Burke’s analysis provides a useful background when considering modern debates over race and politics in popular music. White artists like Iggy Azalea adopt affected performance styles that imitate the music of Black communities, sometimes claiming that they are doing so as a way of paying tribute to that culture. Many white rappers have recorded songs about the Black Lives Matter movement.

“An artist like Macklemore is both earnest and kind of awkward in his songs about the movement. He is kind of being helpful, but also making Black Lives Matter about himself in a way,” Burke noted. “It feels sincere, and that sincerity is the issue with a lot of rock music in the 60s that aimed to be politically radical. What does it mean to sincerely want to be helpful but not quite know what the appropriate tactic would be to make that actually happen?”