From etching copper plates to paper marbling, students in Sarah Weston’s class discover how making art can change the way they understand literature.

When Sarah Weston, assistant professor of English, was a sophomore in college, she found herself engraving metal plates in her parents’ garage, leaving permanent acid stains on their concrete floor. At the time, she was studying the poetry of William Blake, and set out to learn how to create the same kind of illuminated prints Blake once did. The process, which Blake himself called “the infernal method” was messy, difficult, and for Weston, deeply fulfilling.

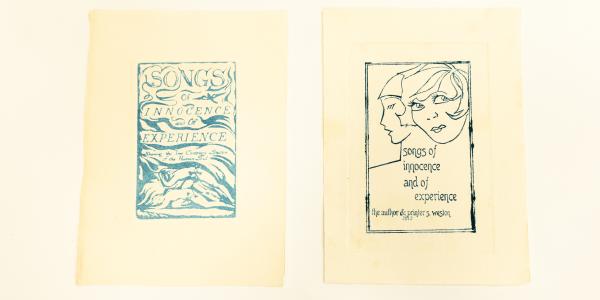

After falling in love with Blake’s poetry, she fell in love with his process of printmaking, apprenticing with a Blake specialist to learn how to relief-etch images on copper plates. Just as Blake had, Weston wrote a set of poems and then illustrated them in the same spirit as “Songs of Innocence and Experience.”

“As a scholar, I thought, ‘How could I possibly talk about Blake if I didn’t understand the visual side of what he was doing?’” Weston said. “Learning his process and being able to replicate it helped me see things in a totally different way.”

Weston, who came to WashU in 2023, is a scholar of the 18th and 19th centuries, with a particular interest in William Blake, Romanticism, and the history of science and mathematics. She’s responsible for the digital humanities project BlakeTint, which allows users to analyze and compare color in William Blake's illuminated books and trace how it has changed over time. She was recently awarded a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) that will support her manuscript about the history of zeroes and ones in the Romantic age.

“There’s something powerful about learning a process and doing it just as they did 200 years ago. It’s a way to feel what others felt, emotionally and creatively.” — Sarah Weston

At WashU, she’s able to experiment with Romantic-era techniques like engraving, paper marbling, and linocutting in her own time, but never imagined she’d be able to fully integrate them into her academic career.

Now, she’s getting her hands dirty inside the classroom, and encouraging her students to do the same. In the survey course she teaches on the literature of the late 18th century to the present (Lit 2152), Weston invites students to engage in numerous creative exercises. Their first assignment is to read one of Blake’s poems and envision a plate based on the poem’s image. Then they look at the plate that Blake designed for that poem, and compare it to their own, which Weston hopes highlights the tension between the visual and verbal in his work.

Students are also charged with writing their own sonnets and sestinas, adhering to the strict mathematical grammar of the forms. They design their own version of the yellow wallpaper from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famed story of the same name, and they write a fairy tale based on Anne Sexton’s poetry.

For Weston, these exercises offer students a “maker’s knowledge,” a spark that can inspire a deeper interest in literature. She believes that experimenting with a variety of formats can illustrate how text behaves differently under different constraints. “When you do things that are hands-on, you learn it better and you see new things,” Weston said.

Weston’s educational philosophy culminates in a new course she created in 2025 called “Scissors, Paper and Pixels: Books and Ephemera, from Blake to AI” (E LIT 420.) The class traces book and printmaking from the 19th century to today. Each week, Weston demonstrates a historical bookmaking technique — everything from Blake-style etching to Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints to hand-binding books with a needle and thread— which students replicate outside of class.

“Because the students create their own illustrations, they read the poems carefully, and they’ll come to me with things I didn’t even notice,” Weston said. “I always feel so lucky to be around my students. They’ve made me see Blake in new ways.”