This semester, Suzanne Loui, a WashU lecturer, is teaching “Fallout: Analyzing Texts and Narratives of the Nuclear Era” in the environmental studies department—and she is not shying away from the polarizing nature of the course’s material. When discussing nuclear technology, public discussion is very divided, and often we hear about risks and not about benefits. This course explores the history of nuclear technology from an integrated point of view. Doing so allows students to navigate an emotionally charged topic through a broader understanding of its development rather than a single, polarized narrative.

In Plutopia, Kate Brown provides the first comparative account of the cities built to support what she calls the “great plutonium disasters” of the United States and the Soviet Union. It is easy to think about Hanford, WA, the site of Brown’s U.S. focus, as an expression of triumphant federal power, and industrial and engineering ingenuity. But that view, according to Brown, distorts the history of the Hanford workers. In Atomic Frontier Days, Bruce William Hevly and John Niemeyer Findlay, on the other hand, look through a wider lens, telling a complex story of Hanford’s state and regional significance, gained through production, community building, politics, and environmental projects.

These texts center on the Hanford Plant, a plutonium production site in Washington State, that was part of the Manhattan Project. Fission had been discovered in 1938, just months before the outbreak of WWII – it was an accidental discovery, and those who happened upon this understood that there was an incredible amount of energy, and therein power, at stake if it could be harnessed. As American scientists and government officials began to understand the implications of this discovery, the question became whether or not we could utilize this information through weapons production, to match our enemies. The decision had to be made rapidly, and at the end of 1942, the US government began to search for a site to work on plutonium production for nuclear weapons. Hanford, a small city in Washington State, became one of three Manhattan Project sites.

Hanford was a good candidate for this work as it had a huge water source, the Columbia River, and an electricity source from the Grand Coulee Dam. Additionally, Hanford was a reasonable distance away from any cities—having this distance was essential when embarking on a project so new and secretive. Within months, the government built the industrial infrastructure within the 600-square mile Hanford reservation, as well as an urban area to house the eventual 50,000 workers in the Tri-Cities of Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco, and the creation and extraction of plutonium began.

Why do you incorporate these texts in particular into the curriculum?

I want students to think critically about the topic—to ask, “How can I practice my skills of listening to understand the whole issue?” Brown is very concerned about the effects of radiation on human health, and about workers’ voices being lost in a more triumphant narrative. Atomic weapons, after all, hastened the ending of the war, so Brown’s concern is that the patriotic narrative overshadows a narrative about human health. For example, in her book she describes the element of top secrecy: many workers at Hanford were not granted access to information about the materials they were handling, beyond the immediate task. One woman Brown profiles was hired to do secretarial work, but once her superiors discovered her aptitude for math, she was transferred to a lab. In the lab, she worked with liquid chemicals, and the superiors would not enter the lab beyond the door, handing her the materials—in other words, those with higher status (and more information) were avoiding coming into direct contact with the radioactive substances. Brown’s overall theme is that the US (and Russian) governments offered workers unusually comfortable, middle class lives (hence the title Plutopia) in exchange for their health.

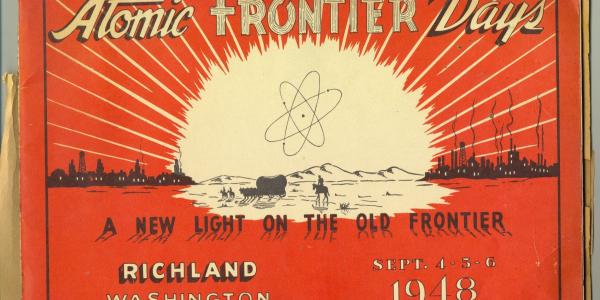

In Atomic Frontier Days, the book taught in conjunction with Plutopia, the two historians Hevly and Findlay attempt to get at something else beyond the triumphant or health narratives: they profile the local, state, and regional economic benefits Hanford brought to Washington State, and the ways in which citizens petitioned government leaders for those benefits (despite the health risks of plutonium production and processing). In working with nuclear technology, Tri-City residents felt they were supporting cutting-edge technology for the good of the country. They saw themselves as operating on the “atomic frontier,” making a significant contribution to America, and they wanted to continue that work.

What do you hope students in your class take away when reading these books?

I hope that students take away an integrated understanding of the Hanford site, applicable to a different type of narrative. A project I assign consists of roleplaying—students pretend that they work for a Washington State environmental division (completely fictional) and have been asked to speak to a group of about 100 citizens who are coming to receive background about Hanford. There will be people in the audience who will be concerned about health, but also people who are very proud of Hanford’s role in the war effort and in state history. As the speaker, the students have to decide what they will say. The task is to create a narrative that fairly represents the concerns of these citizens, in other words, speak to the entire audience. That’s very hard with a charged subject like nuclear history. But an integrated perspective is where the best solutions will form— whether it is food and farming, climate change, what have you.

How did you first hear about these books?

Some years ago, I’d been listening to the increase in nuclear energy debates (due to its potential role in climate change mitigation), and I wanted to better understand the source of the polarized conversations. I saw a book on the shelf about radiation—I knew little about it. It turned out to be written by a doctor who’d been asked to go to Chernobyl to treat the first responders to the reactor accident. Then I began to read Richard Rhodes, the Pulitzer-prize willing historian who has written extensively on the history of nuclear technology; such as The Making of the Atomic,Bomb, Dark Sun, Arsenals of Folly, and Twilight of the Bombs. He talks about how the creation and use of nuclear weapons has coincided with a significant drop in the death toll from, and how its use has the potential to end, major warfare. Honestly, I arrived at these texts from one thing leading to the next. I wanted to really absorb the moral complexities of this issue: the combination of Brown with Findlay and Hevly allowed me to do that.

Why should students who aren’t taking your class read this book?

What’s at stake here is the ability to go beyond that narrow conversation about nuclear technology in the general public. Adopting a simplistic “anti-nuclear” stance inclines one to ignore benefits, while a simplistic “pro-nuclear” stance inclines one to ignore risks. Students need the skills to create new, less polarized narratives about potentially environmentally significant technologies. Exploring nuclear technology through humanities texts offers a good start.

If someone really likes this book or is interested in this topic, do you have any other recommendations?

Anything by Richards Rhodes. And, students might look up the new Manhattan Project National Historical Park – yes, it’s one of our newest national parks