Branson, Missouri, may not fit the mold of other showbiz hubs, but Joanna Dee Das found that its blend of conservative values and variety-show spectacle offers insight into American identity and the enduring appeal of live performance.

Did you know that Branson, Missouri, welcomes more visitors every year than the Louvre? With a population of just over 10,000 people, this small Ozark town annually hosts more tourists per capita than New York City. And in the 1990s and early 2000s, Branson boasted more theater seats than all of Broadway combined.

Despite its staggering popularity and cultural influence, Branson doesn’t receive nearly the same attention as America’s other entertainment capitals. Joanna Dee Das, an associate professor of dance, wondered why.

“I wanted to understand how a small town in the Missouri Ozarks became such a popular tourist destination,” said Das, who also holds faculty appointments in history, African and African American studies, and American culture studies. “I wanted to know what the performances and the messages they’re sending might teach us about ourselves and the world around us.”

In her new book, “Faith, Family and Flag: Branson Entertainment and the Idea of America,” Das explores Branson’s transformation from a small hillside town into a conservative entertainment juggernaut. Her research combines archival work, field observations, and interviews with performers, residents, and journalists to trace the rise in tourism.

It all started in 1907 with Harold Bell Wright’s best-selling novel “The Shepherd of the Hills,” set in the Ozarks, which drew in out-of-towners eager to experience the region and meet its people. Locals started performing a version of themselves for these outsiders, Das said. Meanwhile, nearby Springfield, Missouri, emerged as a hub for country radio, helping to lay the groundwork for the musical legacy that would become part of Branson’s identity. By the late 1960s, local families had opened variety show theaters. Two decades later, country music stars such as Roy Clark had joined the scene.

Today, Branson’s performers specialize in interactive family-focused shows that prioritize audience engagement and build a strong sense of community. Das said this kind of theater and its participatory spirit resemble how most performances operated before the mid-19th century.

“Variety shows and vaudeville were the original TikTok,” she said. “Our social media consumption today shows the enduring love for a Branson-style show.”

Beyond its theatrics, Branson presents itself as grounded in three fundamental American values: religion, family, and patriotism. But, as Das noted, these take specific forms in Branson. “It’s a Christian faith, a view of family defined narrowly by heterosexual marriage, and a strong dedication to the nation, especially the military,” she said. Many of the Branson residents and tourists who have embraced these values over the decades have felt marginalized in modern American culture, Das found, a dynamic that helps explain both the content of the town’s shows and the loyalty of its audiences. Branson has offered them a place to feel re-centered in the story of America.

“When you go to a Branson show, there isn’t as much of the resentment rhetoric that you often see in right-wing media,” Das said. “It’s a positive message of community and connection, which is one that is struggling to stay relevant in our current political moment.”

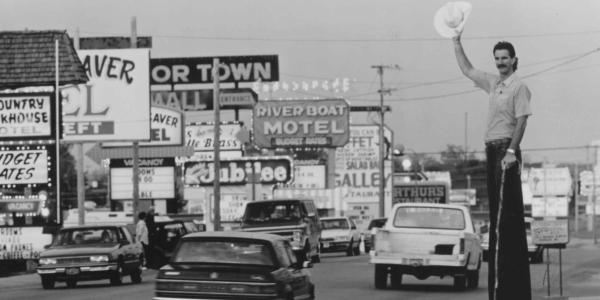

Header image: “The Tallest Texan” advertising The Texans Show along the Branson Strip in the late 1980s (Credit: White River Valley Historical Society).