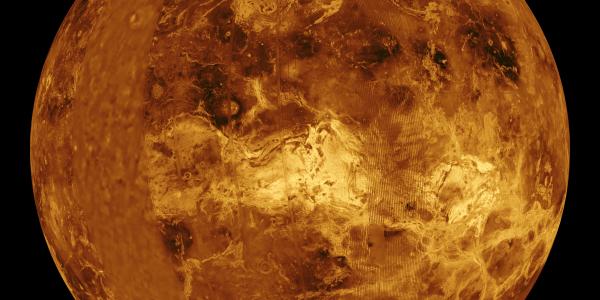

New calculations by Arts & Sciences researchers suggest surprising geology beneath Venus’s surface.

Venus — a hot planet pocked with tens of thousands of volcanoes — may be even more geologically active near its surface than previously thought. New calculations by WashU researchers in Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences suggest that the planet’s outer crust may be constantly churning, an unexpected phenomenon called convection that could help explain many of the volcanoes and other features of the Venusian landscape.

“Nobody had really considered the possibility of convection in the crust of Venus before,” said Slava Solomatov, professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences. “Our calculations suggest that convection is possible and perhaps likely. If true, it gives us new insight into the evolution of the planet.”

The paper was published in Physics of Earth and Planetary Interiors. Chhavi Jain, a postdoctoral fellow, is a co-author.

Convection, a well-known process in geology, occurs when heated material rises toward a planet’s surface and cooler materials sink, creating a constant conveyor belt of sorts. On Earth, convection deep in the mantle provides the energy that drives plate tectonics.

Earth’s crust, about 40 km thick in continents and 6 km in ocean basins, is too thin and cool to support convection, Solomatov explained. But he suspected the crust of Venus might have the right thickness (perhaps 30 km to 90 km, depending on location), temperature, and rock composition to keep that conveyor belt running.

To check that possibility, Solomatov and Jain applied new fluid dynamic theories developed in their lab. Their calculations suggested that Venus’s crust could, in fact, support convection, a whole new way to think about the geology of the planet’s surface.

In 2024, the two researchers used a similar approach to determine that convection likely does not happen in the mantle of Mercury because that planet is too small and has cooled significantly since its formation 4.5 billion years ago.

Venus, on the other hand, is a hot planet both inside and out. Surface temperatures reach 870 degrees Fahrenheit, and its volcanoes and other surface features show clear signs of melting. Scientists have long wondered how heat from the planet’s interior could be transferred to the surface. “Convection in the crust could be a key missing mechanism,” Solomatov said.

Convection near the surface could also influence the type and placement of volcanoes on the Venusian surface, Solomatov said. In 2023, Paul Byrne, associate professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, published an atlas of 85,000 Venus volcanoes based on radar images from NASA’s Magellan mission from the early 1990s. Solomatov said he and Byrne have discussed possible future collaborations that would combine mathematical modeling with observations of Venus’s surface for a better understanding of the planet’s geology.

Solomatov hopes future missions to Venus could provide even more detailed data on the density and temperature in the crust. If convection is occurring as expected, some areas of the crust should be warmer and less dense than others, differences that would be detectable using high-resolution gravity measurements.

But perhaps an even more intriguing target is Pluto, the frozen dwarf planet at the outer reaches of the solar system. Images from the New Horizons mission revealed remarkable polygonal patterns on Pluto’s Sputnik Planitia region that resemble plate boundaries on Earth. These polygons are formed by slow convection currents in a 4 km-thick layer of solid nitrogen ice. “Pluto is probably only the second planetary body in the solar system, other than Earth, where convection that drives tectonics is clearly visible on the surface,” Solomatov said. “It’s a fascinating system that we still need to figure out.”