Michael Bouchard, PhD ’19, is playing a critical role in the Mars Sample Return campaign being planned by NASA and the European Space Agency that seeks to collect rocks from the red planet and carry them back to Earth.

Michael Bouchard, PhD ‘19, is part of a global team that is preparing the greatest rock-hunting expedition in history. As a payload systems engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, he’s playing an important role in the Mars Sample Return campaign, an ambitious project that aims to deliver rocks from the surface of Mars — specifically within and around Jezero Crater — to labs on Earth.

“I’m honored and privileged to be doing my dream job,” Bouchard said. “This mission is a generation-defining technical challenge. My training at WashU has put me in a place where I can contribute.”

Bouchard has long had his sights on space. As an undergrad at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, he studied satellite images of Egyptian deserts with the goal of eventually graduating to the deserts of Mars. He also gathered a group of fellow students who built Mars-style rovers from scratch. “We built our own power systems, printed circuit boards and designed robotic arms, and took them out to the desert of Utah for international competitions,” he said. “Our first rover barely moved, but we took second place in the world the next year.”

Bouchard got his first shot at real space science as a WashU PhD student when he joined the lab of Bradley Jolliff, the Scott Rudolph Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Science. Jolliff’s research on Mars and his long-standing collaborations with NASA gave Bouchard a chance to work with data from Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity, real Mars rovers with a serious purpose.

For his dissertation, Bouchard analyzed data from the alpha particle X-ray spectrometers mounted on each of the three NASA rovers that provided insights into the geologic history of Mars. “We had an incredible opportunity to look at hundreds of rock samples from different places across the planet,” he said. “I built statistical models to quickly compare different rock types, classify them, and group them.”

As much as he enjoyed the science of planetary discovery, Bouchard started to develop a new passion midway through his PhD studies. Instead of approaching space purely as a scientist, he wanted to take on the challenge of engineering. “I thrive in a fast-paced team environment, and I enjoy working with engineering teams working together to solve problems,” he said.

With Jolliff’s help and encouragement, Bouchard landed an internship at JPL, a global leader in space engineering. In 2019, he was hired full time. While he was eager to continue Mars exploration, he first took a detour to Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter. Europa has long intrigued planetary scientists because the ice on the moon’s surface covers vast oceans of liquid water that could potentially provide a habitat for extraterrestrial life.

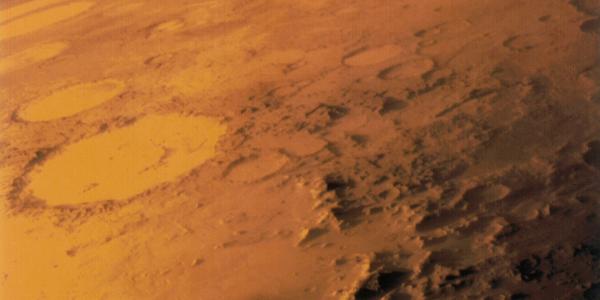

(Image: NASA)

For two-and-a-half years, Bouchard was a payload systems engineer for the Europa Clipper, a NASA orbiter that is set to launch in 2024 on a mission that will use radar to explore the moon and its ice-covered oceans. As a systems engineer, Bouchard took a big-picture view of the spacecraft to make sure every component — batteries, antennae, radar systems, and more —could work together in the extreme magnetic field that surrounds Jupiter. “The team realized early on that the magnetic field was one of the biggest threats to the mission,” he said. “With a complex problem like a spacecraft, you have to break it down into still very complex pieces and make sure all those pieces come back together.” For his efforts, Bouchard shared in two JPL Voyager Awards, given to recognize technical contributions to a mission.

In 2022, Bouchard returned to the red planet by joining the Mars Sample Return campaign, which includes a planned three-spacecraft program to bring back samples collected by NASA’s Perseverance rover. Bouchard is working on the Sample Return Lander that is scheduled to launch as early as 2028. Specifically, he is working on the lander’s camera system and sample cache that will hopefully carry the rocks from the Martian surface to orbit. From there, the cache — and the Martian rocks inside — should be captured and returned to Earth. Being able to handle and study the Martian rocks up close will transform our understanding of the planet, Bouchard said.

Bouchard isn’t the only researcher with WashU credentials who is supporting Mars Sample Return. In August, NASA and the European Space Agency named Ryan Ogliore, associate professor of physics, and Kun Wang, associate professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, as members of the Measurement Definition Team. The pair will participate in assessing the measurement and instrumentation needs for the NASA-European Space Agency Sample Receiving Project, which seeks to develop a high-containment facility to process the Mars samples once they arrive. And Meenakshi Wadhwa, PhD ’94, has been named the principal scientist for the Mars Sample Return program; she will discuss the importance of bringing Mars samples back to Earth as part of the Robert M. Walker Distinguished Lecture Series in late October.

While Bouchard’s path from Missouri to Mars and beyond may seem circuitous, he said everything fell into place as soon as he arrived at WashU. “It was pretty much a straight line from WashU to JPL,” he said. “I was really fortunate to get in the door.”