Junior Zeina Daboul shares how a comparative literature course redefined how she approaches problems — and her own varying interests.

in Data Science in the Humanities (DASH) and communication

design. She is interning as a digital humanities research assistant

with Assistant Professor of English Gabi Kirilloff and postdoctoral

research associate Claudia Carroll. (Illustration: Kristen Wang)

When I was in high school, I felt like I had to shrink my world into a single, predetermined path where all subsequent choices had to fit a narrative that led to medical school and a career as a pathologist. I joined the national science honor society, the national math honor society, the volunteering club, and the medical club. Everything I did was to build the perfect resume that showed a sincere dedication to medicine.

But I had other interests. Reading books and editing essays? “Yeah, that’s just a hobby,” I told myself. Digital design, the class that was the most gratifying of my high school career? “That can stay on the sidelines.” The barely functional HTML websites I spent hours working on? “They’re not serious.” I entered high school knowing what the next 10 years of my life would look like, and those hobbies had no place in it. By the end of the 11th grade, I realized my single-minded pursuit of medicine would come at the sacrifice of everything else I enjoyed, creating a one-dimensional individual.

When I came to WashU, I discovered that computer science offered something medicine could not: the fluidity and flexibility to discover intersections between fields and, more importantly, to create my own. I studied AI, cybersecurity, and web design. I met others who floated between disciplines, a reality unimaginable when I was in high school.

One of those students was a close friend studying computer science and English, majors I initially saw as incompatible. English is a personal study, requiring close reading and meticulous examination. It’s nuanced, ornate, and innately human. Computer science, on the other hand, is mathematical and formulaic. How could two contradictory areas effectively combine?

explore literary bias and style in GPT, an AI model that processes and

generates human-like text.

My perspective shifted drastically when my friend introduced me to the digital humanities. At the time, she was taking “Introduction to Digital Humanities” with Gabi Kirilloff, an assistant professor of English. Students in the course used web scraping and other computational methods to look at the usage of Eurocentric terminology in Wikipedia entries.

I can’t imagine a better introduction to the field. My friend was investigating topics I was interested in, using digital tools I was familiar with, and arriving at conclusions that would have normally required months. Data science, I learned, could be a powerful tool for answering humanistic inquiries. My own experience with the course the following semester solidified this understanding, especially when Claudia Carroll, a postdoctoral research associate co-teaching the class, tasked us with writing an essay about the history of AI using ChatGPT.

I knew ChatGPT’s writing skills weren’t brilliant but I didn't expect them to be quite so lacking. I fought with the machine to arrive at a somewhat effective outline of an essay. The initial drafts were littered with circular reasoning and repetition. ChatGPT presented no concrete ideas and ended almost every paragraph with the same platitude: “Assessing creativity in AI is a complex matter.”

This unusual assignment illustrated the process and nuances of blending technology and humanistic inquiry. Working this way is not an abandonment of traditional literary analytical methods. Instead, I found that using AI necessitated a heightened — and deeply human — process of analysis and revision.

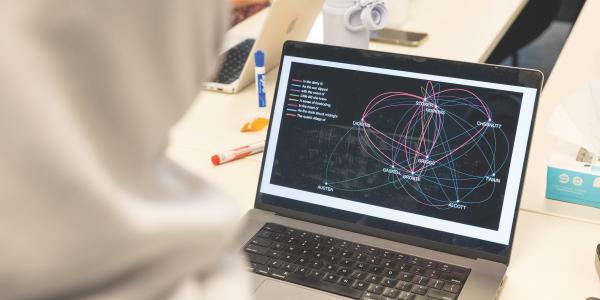

The method I used for the essay was integral to my work on another project with professors Kirilloff and Carroll: an investigation of AI and literary style. Reading AI-generated passages in the style of famous authors engaged analytical skills I had used since grade school while also challenging my understanding of literary concepts: What measures best quantify similarities between sentences? How can we best convert a word, sentence, or paragraph into data? Are those numerical representations even accurate?

Thanks to my earlier coursework in computer science, I had the technical skills to analyze the generated text using a variety of methods. Applying those techniques, however, required the literary proficiency to recognize when the outputs were wrong. I had to approach problems from multiple perspectives and in new ways.

This research experience reinforced my commitment to avoiding the same single-mindedness that had characterized my high school career. It proved to me that my interests do not have to exist in isolation. My identity as a reader can work in conjunction with my technical abilities and creativity. This realization has transformed my understanding of the two fields. An interdisciplinary approach can reveal insights that would be impossible to answer using either lens alone.

Bridging the divide between the humanities and data science will answer some of the most important questions about the human experience, past and present. I’m excited to be a part of it.

This story appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Ampersand magazine. See more stories from the magazine and browse our archives.