Graduate students at WashU explore translation as a creative practice that can lead to unexpected convergences and new creative endeavors. WashU's Program in Comparative Literature houses a graduate track for international writers that provides a space for established translators and writers to develop their practice within a scholarly context. It is one of the only of its kind in the world.

Of all of the books published in America each year, only about three percent are works in translation. The percentage of fiction and poetry in translation is even lower, at less than one percent. This publishing culture is starkly different than that of European countries like Germany, Italy, and France, which all have much more robust markets for works in translation.

What could Americans be missing out on by not exposing themselves to literatures written in other languages? Potentially, quite a lot. According to some of the translators studying comparative literature at WashU, translated works can introduce different styles and forms of writing to completely new audiences, which can inspire writers of the receiving language in unexpected and exciting ways.

For readers and writers who only operate in a single language, the act of translation may seem like a purely technical endeavor. However, according to Noh Anothai, a third year doctoral candidate, the exact equivalency between words that we often see in language textbooks does not really exist, making translation more of an art form that incorporates both the original author’s voice and the voice of the translator. “I think that people don’t consider how much work the translator goes through sifting the options and fitting the word to the context,” he explains. “It can come across as mechanical when in reality it is a really nuanced process.”

Matthias Göritz, professor of practice of comparative literature and the first graduate of the new track, echoes that statement, saying that the product of translation is never an exact replica of the original work. “The text which comes into being through the process of translation ideally is something new, something third, it’s not the original anymore,” he says. “It is not only a German poem or a German novel, it is something kind of like where the original and the voice of the translator meet and create something like a new perspective for the language and the readers. And that is very exciting.”

Göritz is originally from Germany and has translated a number of works into German from a variety of languages, including English, French, Russian, and Slovanian, among others. One of his more recent translations was a German translation of the poetry of Mary Jo Bang, professor of English at WashU. Bang has also translated Göritz’s work, and in fact recently received the 2018 Gulf Coast Prize in Translation for her translation of his book of poems, Colonies of Paradise. Göritz worked closely with Bang on both of their translations, and he enjoys seeing the way their voices meld in their finished products to create something unique and different. “The translator is the best reader of the author’s work, or tries to become the best reader of the author’s work, and then he or she also becomes the best rewriter of the author's work,” he says in regards to their collaboration. “The intimacy that is created by this, and the process that starts there, spark a very interesting translation if the translator and the author can collaborate and can communicate, and in Mary Jo’s case and mine it is working… and that is very rewarding.”

Göritz, who is a prolific author of both poetry and fiction, sees his translation work as being as important as his own writing in contributing to his home country’s literature. “I select the poets I translate asking… is this adding something to the German discourse of poetry, is it adding something to the German language or the German approach of how we perceive poetry?” he explains. “It is a kind of enrichment of my native language by translation, that is what I feel is as important as writing myself.”

Anothai shared similar sentiments about his translations from Thai to English, saying that he hopes that other authors will find inspiration in the works he translates. Anothai’s largest project to date has been translating and publishing Poems from the Buddha's Footprint by Sunthō̜n Phū, a nineteenth-century Thai poet who is sometimes referred to as the Thai Shakespeare. Anothai explains that Phū was a master of the Thai nirat form, which has some resemblance to the travel memoir but with its own conventions, and he would like to see this form influence literature written in English. “I think it would be so interesting to see people write nirat but not in Thai, making their own stories and language backgrounds to conform to this particular genre of Thai writing,” he states. “I think it would be really cool to see hybrid work being produced.”

Both Anothai and Göritz were already established translators before they began graduate work at WashU, but they note how being in the program has enriched their translations in new ways by bringing them in contact with other scholars and authors around the world. “Before I would have said the most seamless translation into English is the best translation, the one that sort of effaces any cultural or linguistic difference, and while those might be the easiest to read, I think I have come to an appreciation of how that is not always the best standpoint to take,” Anothai explains. “I think sometimes you want a translation that can be subversive, you want a translation that will challenge the receiving language, to stretch the possibilities of that receiving language.”

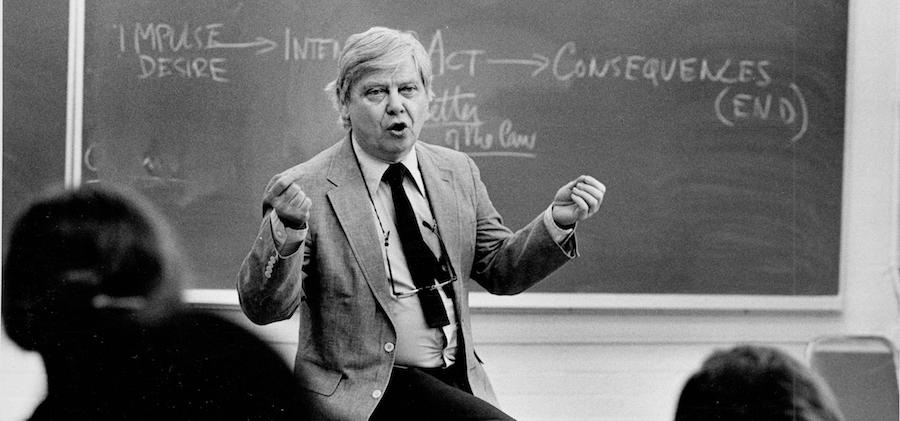

The international writers track is itself like a work in translation in that it is a meeting of cultures, to the potential benefit to all of their literatures. Lynne Tatlock, professor of German and Hortense and Tobias Lewin Distinguished Professor in the Humanities, as well as a translator herself, first began conceptualizing the new track back in 2012. With the support and collaboration of numerous colleagues and deans, she began to move forward with it experimentally in 2013. The idea was to create a new type of PhD program that could allow for more dialog between academics and international creative writers as a revival of the International Writers Center that William Gass had organized on WashU’s campus decades before.

The Writers Center had sought to bring together writers from all over the world to discuss the art of writing and potentially collaborate on new projects. Comparative Literature has attempted to replicate aspects of this mission with aspiring writers. Matthias Göritz, who was an established writer but did not yet have a PhD, became the program’s first student, and collaborated with Tatlock on producing and teaching its core course, “Literature in the Making.”

The program, like any good work in translation, allows unique connections to be formed, not only between students from different countries and origins, but also among academic departments in the university. Students in the program are not very restricted in the classes they take, and so end up making intellectual connections throughout the University and being advised by professors in a variety of departments, including English, German, Romance Languages, Chinese, Japanese, and Classics. Tatlock says that the interdisciplinary nature of the program is good for the professors as well as the students. “It makes these networks that normally might not exist on campus, it overcomes the siloing that one inevitably has in one’s home department,” she says.

Both Tatlock and Göritz have been impressed with all of the new networks and publications that have come out of the program just in the last few years, and see the international writers track as the start of something that will reach far beyond the university. Aaron Coleman, a doctoral student in comparative literature and Chancellor's Fellow, is translating AfroCuban poet Nicolás Guillén’s 1967 poetry collection El gran zoo (The Great Zoo), exploring how literary translation mediates relationships between Afrodescendant peoples from different countries in the Americas. Fellow doctoral student Jae Kim recently won the inaugural Poems in Translation Contest and published his translations of poems by South Korean poet Lee Young-ju on Words Without Borders and Academy of American Poets. Göritz envisions that WashU might become a hub for translators, a resource that people working in disparate countries and languages can call on to connect them with people who are doing work in a particular language or culture. He says of the program, “Nobody wants streamlined literature, but I would also say nobody wants streamlined academia, and I think this program is really trying to invent something… that is really about diversity just by its idea, to be a world hub and a world network of writers and translators coming together.”